Building the Digital City

Back to Urban Research & Development Strategy

The first major study of the impact of New York’s new tech industry on the city’s physical landscape, a 2013 research and conference initiative that introduced the notion of an “urban digital culture.”

Building the Digital City: Tech & the Transformation of New York, a 2013 research and conference initiative exploring the rise of the tech industry in New York, was developed by James Sanders for the Center for Urban Real Estate (CURE.) at Columbia University’s Graduate School for Architecture, Planning and Preservation. The study, co-produced with Arup, was presented at a daylong conference in November 2013 which drew 250 participants and panelists, including many significant figures in the city’s tech, architecture, and real-estate sectors.

Alejandra Rangel Smith, NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management

#Interpreting the City

Building the Digital City was prompted by one of the most striking—and unexpected—developments of the past two decades: the emergence of a new kind of urban tech culture, entirely distinct from the 20th century model of Silicon Valley (above left), and centered not in low‐density, auto‐centric suburban office parks but dense, pedestrian‐ oriented, mixed‐use urban districts (above, right). In New York, the emergence of this new culture has been propelled by the explosive growth of the city’s tech industry, which by almost any measure—the number of funded start-ups, the success of its fastest-growing companies, the meteoric rise in venture capital, the boom in leasing, and, not least, the growing gravitational attraction it is exerting on established West Coast tech giants—has become not only a leading engine of growth but also a transformative urban force, redefining the very nature of city life and work in the 21st century.

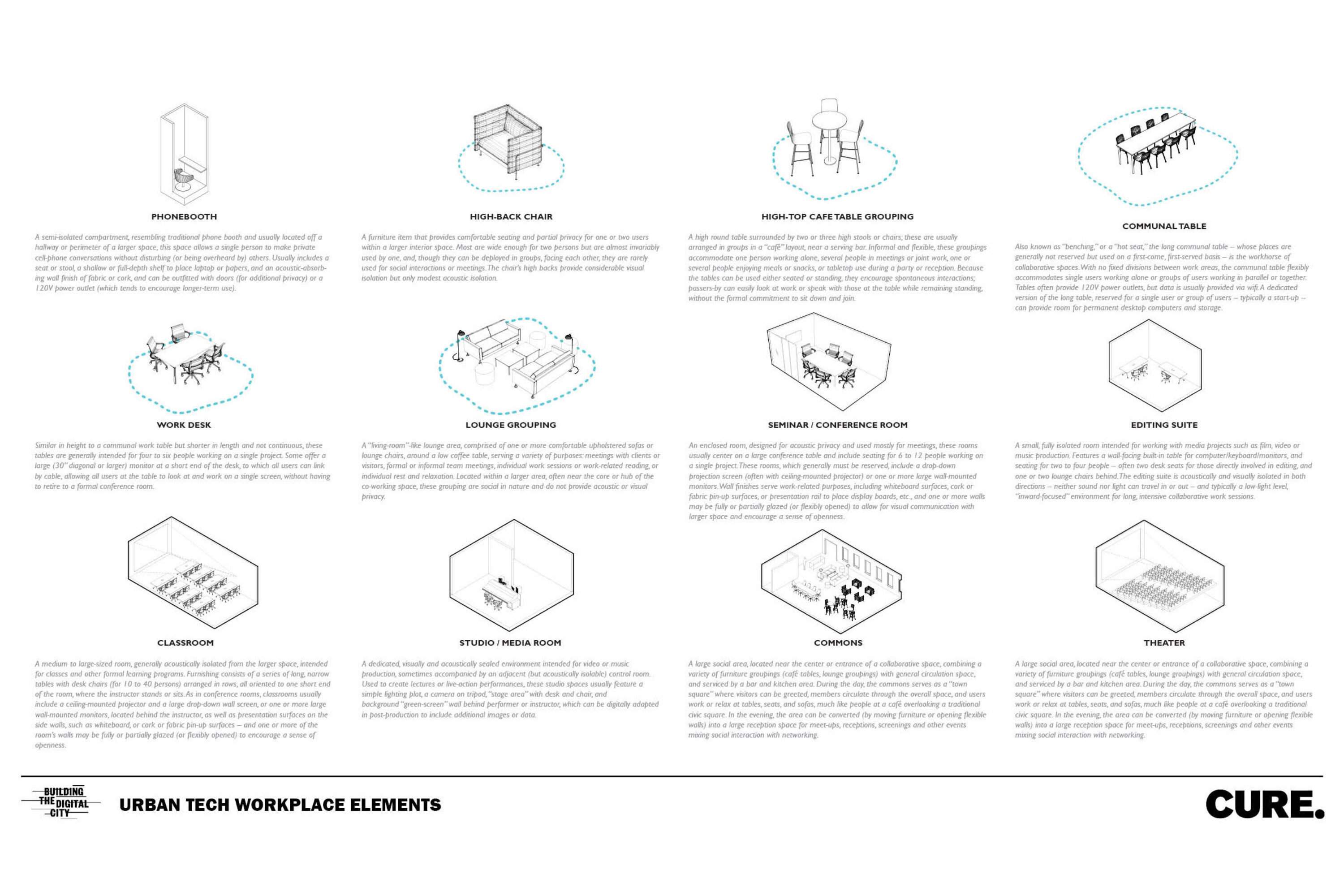

To apprehend the new urban tech culture, Building the Digital City studied its impact at a wide range of scales, rising step-by-step from the workplace, to the building, to the district, to the city—recognizing that its innovations interlock tightly with one another, with smaller-scale changes having a clear and causal impact on larger ones. At the scale of the workplace, for example, it has pioneered innovations through new collaborative models, including coworking spaces, that are reshaping basic notions about the layout of the urban office and the process of working. The research included a diagrammatic analysis of the variety of working environments within these new spaces (above), which in some ways resemble a university library more than a traditional office floor. (See enlarged diagram here.)

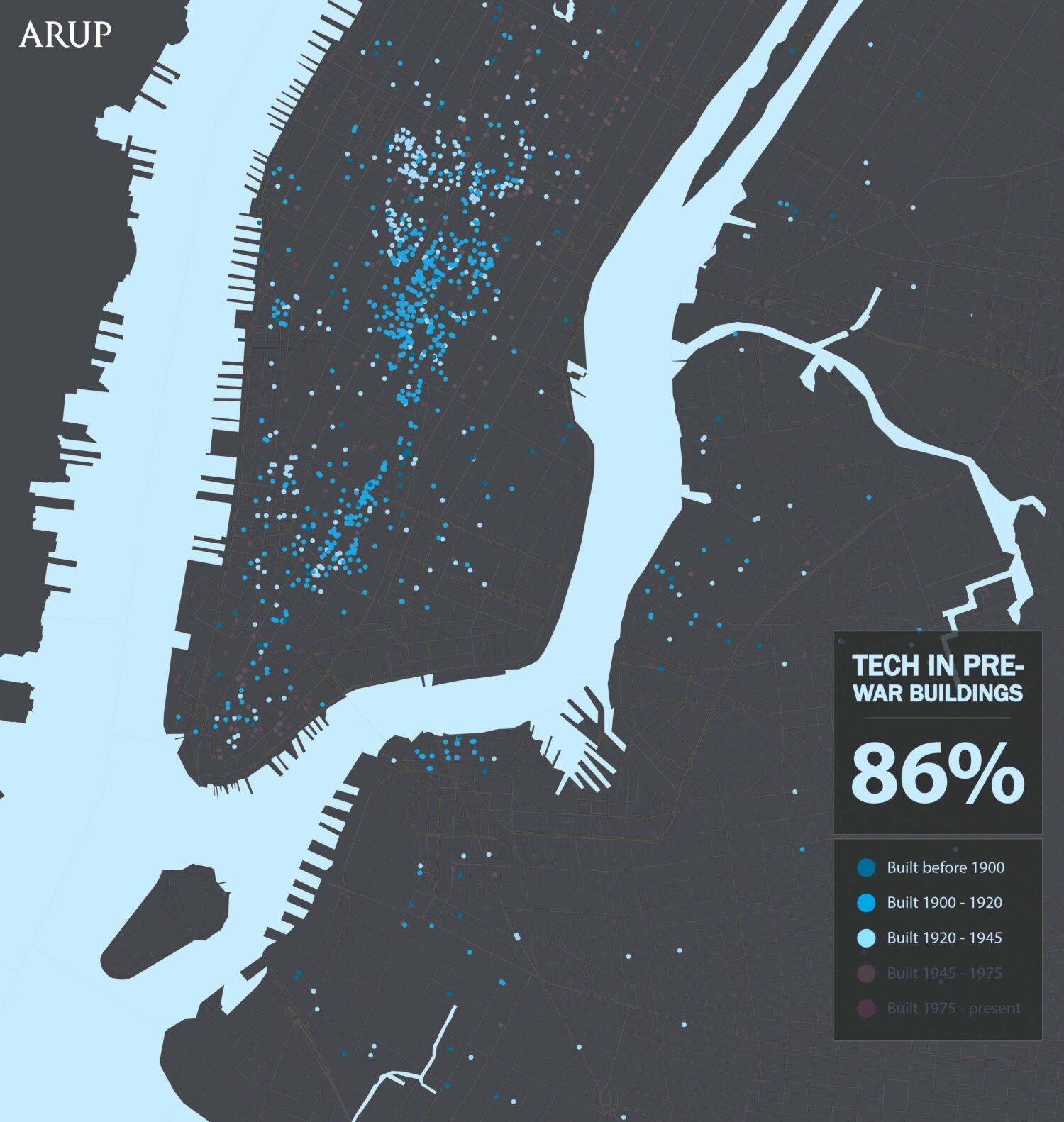

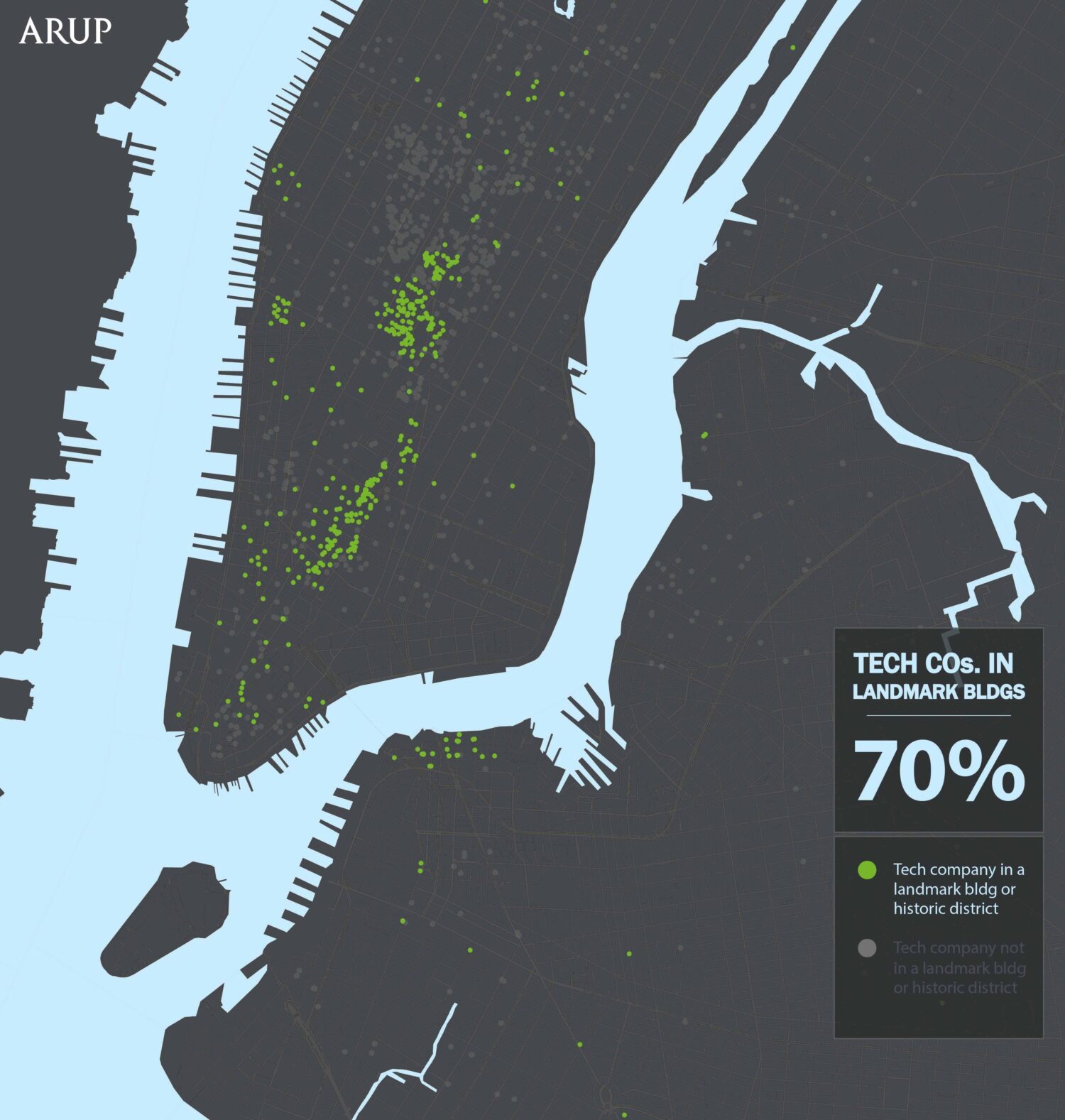

Moving to the scale of the tech-oriented neighborhood, the research uncovered a remarkable finding through a mapping study of the tech industry’s preferences of location and building type. “New ideas require old buildings,” Jane Jacobs observed half a century before, but the study revealed just how decided the tech industry’s preference for older structures had become: 86% of tech companies in New York in 2013 were located in structures built before 1945, and 70% in designated landmarks or historic districts. These results offer significant policy implications—not least for the Landmarks Preservation Commission, sometimes dismissed as a backward-looking agency, but in reality perhaps one of the city’s most effective economic development tools in attracting this growing, cutting-edge commercial sector.

The new tech culture stands in striking contrast to the city’s postwar business districts, filled with immense, self-contained corporate office towers—which, though located in the center of the city, remained internalized environments, complete unto themselves, requiring almost no interaction with the world around them. The tech start-up workplace, by contrast, represents an incomplete space, not an inward-facing fortress but an outward-facing “perch” from which to alight into the larger environment—which itself is part of the tech workplace. In this new understanding, the elements of the city’s ground-floor public domain—its cafés, hotel lobbies, parks and plazas—are no longer simply “amenities,” supporting a business district’s quality of life; they are the site of business itself, where one’s office is sometimes located, and work is carried out singly or in groups.

See full report here.